The Ocean: the Great Provider

- Erin Pamplin

- Oct 7, 2023

- 4 min read

An exploration of the significance and applications of archaeology in understanding human relationships and interaction with marine resources throughout time in Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Launching of TePuke, a traditional proa built as part of the Vaka Taumako Project, using traditional methods, materials, and designs.

There are two ways one can view the ocean, as a divider or as a connector. In Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific, the latter is the reigning perspective. The ocean is a connector, touching all islands and linking all communities. It is a source of life and opportunity, as many communities of both past and present heavily rely on marine resources to sustain themselves economically, physically, and culturally.

There is a wide range of methods developed to optimize a variety of marine resources including shellfish, urchins, turtles, mollusks, sunfish, tuna, swordfish, reef fish, and sharks, to name a few. Some communities also practice marine mammal hunting of dolphins, porpoises, and whale sharks. In Eastern Indonesia, there are two communities based in Lembata and Lamalera that still practice whaling today, with Lamalera harvesting roughly 20 sperm whales a year. The types of resources harvested along with the associated technologies and methods have been honed from hundreds, and in some places, thousands of years of practice. Understanding these methods of past and how they connect to present practices can serve to revitalize and strengthen indigenous knowledge systems, aid in the conservation of threatened marine habitats, and build climate reliance in impacted areas.

The utilization of marine resources can be seen within the archaeological record through the analysis of discarded/preserved shells, bones, tools, canoes, and site formations. By counting the minimum number of individuals of marine species and identifying the species present at a site, archaeologists can understand what marine organisms were a part of past diets as well as how the diet changed throughout time. This combined with other ecological and paleontological data can provide insight into the climate during the time of occupation and how it may have impacted marine and human populations.

The presence of offshore organisms can also indicate how far people were traveling to obtain the marine resources present in sites and what technologies were developed to facilitate this. For example, tuna are found offshore at deeper depths than reef fish. If tuna bones are found at a site, then it can be inferred that people had canoes strong enough to sail past the break into the more open ocean, and stable enough to stay upright while fighting a fish and swaying in well. It also means they possessed the knowledge of voyaging, navigation, and fish movement and behavior in order to effectively harvest this resource. For this reason, it has been proposed that one of the motivators behind island settlement and ocean voyaging was the tracking of tuna and/or the need to seek other fishing sources when local ones were stretched or threatened. Similarly, by comparing tool technologies across sites, archaeologists can begin to piece together potential settlement patterns and routes as information and technologies were spread by voyaging and trading people.

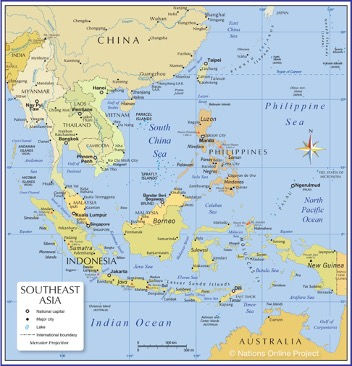

Map of Island Southeast Asia (left) and Oceania (right).

Today, many places in the Pacific Islands are still dealing with the effects and continued practice of colonialization. Ancestral knowledge of cultural practices, voyaging, navigation, languages, interisland relations, fishing grounds and techniques, traditions diets and dishes, and stewardship of native habitats is threatened by the forceful push towards industrialization, globalization, and a reliance on imported and processed goods. It has increased health issues, malnutrition, poverty, habitat destruction, and decreased biodiversity. Maintaining, strengthening, and practicing ancestral knowledge works to directly combat the threats of climate change and colonization.

Archaeology can assist in supporting and adding to ancestral knowledge by researching how people have utilized and cared for terrestrial and marine environments. On Molokaʻi Island in Hawai’i, archaeological surveys found several sites that were fishponds for aquaculture and fish farming. They were able to learn how the natural landscape was modified to support these sustainable farming practices which could then be reapplied to present practice. This type of information can be used to advocate for the protection and access to ancestral fishing and agricultural grounds.

In the Solomon Islands, there is a project called the Vaka Taumako Project that is working to teach, practice, and document ancestral voyaging knowledge. With a combination of embodied knowledge, archaeological research, and known traditions, they are building sailing canoes with entirely traditional methods and materials and teaching men, women, and children navigation and voyaging. In these ways, archaeology can supplement and support the continued practice of ancestral knowledge and work to protect marine environments and lifestyles. Just as the ocean links together the world’s islands and continents, archaeology can bridge together the knowledge and peoples of the past and present.

References

Egmai, Tomoko and Kojima, Kotaro

2013 Traditional Whaling Culture and Social Change in Lamalera, Indonesia: An Analysis of the Catch Record of Whaling. Senri Ethnological Studies. Vol 84. 155-176.

George, Marianne

2021 Ancestral Voyaging Knowledge in Oceania II: Pacific Women’s Knowledge. Paris: UNESCO Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS).

Kirch, Patrick & Dye, Tom.

1979 Ethnoarchaeology and the development of Polynesian fishing strategies. The Journal of the Polynesian Society. Polynesian Society (N.Z.). 88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20705394?origin=JSTOR-pdf.

Kurashima, Natalie, and Patrick V. Kirch

2011 Geospatial modeling of pre-contact Hawaiian production systems on Molokaʻi Island, Hawaiian Islands. Journal of Archaeological Science. 38:12. 3662-3674. doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.08.037.

Comments